Front entrance of the Kamloops Indian Residential School, built in 1923. This building stands as a solemn reminder of Canada’s residential school system and its enduring impact on Indigenous communities.

My enrolment in the course on human rights and social justice was a profoundly transformative experience that changed the course of my studies.

The course module session I found to be the most interesting was the Indigenous studies with Dr Jenna Woodrow and Tracy Strain. The course was full of experiential learning, and the first class with Elder Doe Thomas telling us how traditional smudging is done, and the ceremonial introduction was powerful. Elder Thomas gave profound information on the significance of Land Acknowledgement. Such an experience was more than the standard cultural education; it was a thought-provoking journey into an intergenerational, ritual practice, which enlightened the historical paths being pursued by Aboriginals and served as a guide to a better tomorrow.

We had the opportunity to be in class with Elder Horace Eustace, who taught us the building blocks of the Secwepemc language. The greetings like (Weyt-k, ren skwekwst Rosemary- Hello, my name is Rosemary). The personal connection to the linguistic and cultural background of the Secwepemc community directly appealed to me.

We had the ultimate experience during the visit to the Kamloops residential school at 345 Chief Alex Thomas Way, Kamloops, British Columbia. The unending injustices that were being inflicted on the Indigenous people by the Canadian state became too perceptible. As the biggest residential school in the country, the institution, today, is a chilling account, even now, of cultural genocide and institutionalised oppression. Its walls remain, yet they resonate with the profound feeling of loss, dispossession, and betrayal of generations of Indigenous children forcibly removed from their families. Physical, emotional, spiritual, and sexual abuse continues to resonate to date, as it is important to note that the children of Indigenous people are overrepresented in the foster care system, which, today, is a new form of colonial violence.

The building itself, on its part, not only maintains a policy of historical assimilation but also actively employs a system of colonialism that seeks to eliminate the Indigenous identities, languages, and territorial relations. The experience of the visit to the site was both a chilling experience of long-term trauma and also a reminder of how the Secwepemc people and other Indigenous peoples in this country can resist and reclaim their past, their cultures, and their language. This encounter cemented the idea of social justice, focusing on the past and present injustices and the recognition of the truth about the Indigenous experience, as well as supporting the healing, restitution, and decolonization process.

In the course with Dr Lisa Cooke and Dr Robin Westland, we went for a field trip to the Same Sky Collective Society on 417 Tranquille Road, Kamloops. Being in the studio, I felt the place full of voices and stories, and united in a place that was specifically designed to enhance inclusion and belonging. In the context of viewing art objects and making experiences, the understanding of the concept of mapping a place was redefined as a word closely related to the history of land dispossession, migration, and resilience.

Talking to Lana in her studio and especially about her final project, I was reminded that we all are stories written on lands, waters and nature, a more weighty, more complex dimension, in which my presence and movement in this geospatial reality is only a fragment of a greater narrative of settler colonialism, in which privilege and responsibility are to be viewed equally.

This is what has made me more sincere and humble in my mapping assignment. Rather than establishing my personal milestones or my memory alone, I am in the habit of citing the history, past injustices, and present-day relations with the Indigenous people that shape the locations that I call home. This upbeat, creative atmosphere of the studio was my place to reflect on how art can make it possible to discuss the problematic reality, establish a conversation, and understand more about how to be a better and more responsible individual to live on the shared ground.

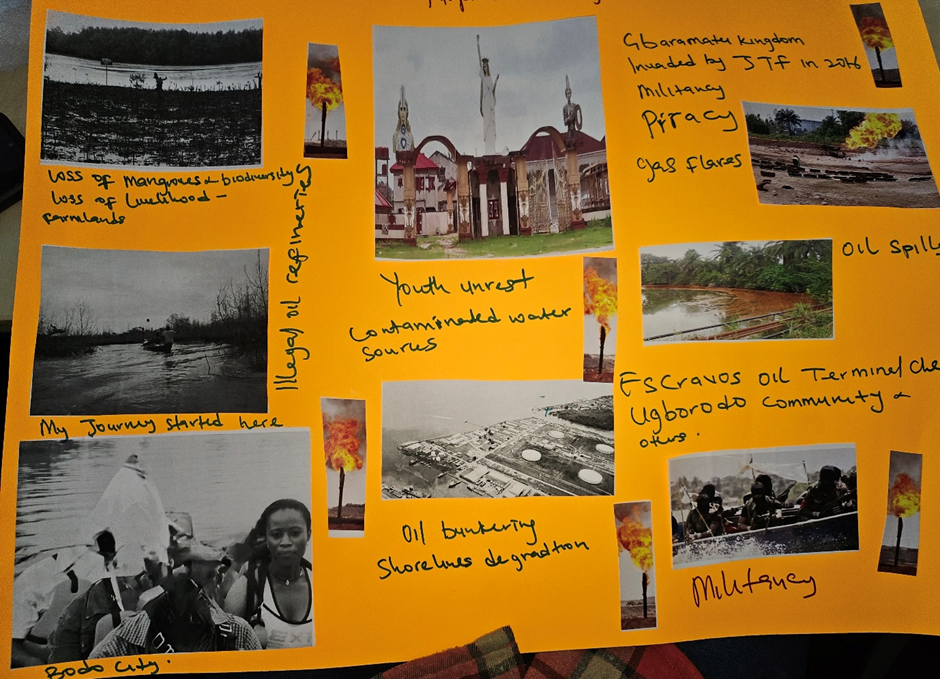

As a community-based worker back in my home, Nigeria. My experience in the oil-rich Niger Delta, where I developed as an activist, feminist and advocate. It was a learning place, besides being a place of work, with the natural world appearing complete and rich. Nevertheless, as the years passed by, I saw how the environment was deteriorating, the oil spills had not only polluted the water and the gas flares the air, illegal refineries with carbon gases became the hallmark of a desperate effort to make a living in an already exploitative environment.

These ecosystems’ communities that lived sustainably became increasingly affected by the theft of resources, marginalisation, youth restlessness, and militancy, which was a form of protest over the neglect and the failures of the past and present governments. My map was based not only on the geographical tracks but also on the intersecting filaments of loss, survival, and outlook. The map has been dedicated not only to the places I have been but also to the issues and problems that characterise the Niger Delta and its people, who have remained attached to the lands.

My map: My Journey through the Niger Delta

Reference:

Tk̓emlúps te Secwépemc. (2024). Kamloops Indian Residential School National Historic Site designation. Retrieved from [https://tkemlups.ca](https://tkemlups.ca)